Americans Get an F on Digital Privacy Knowledge

Only 22% of Americans can identify the types of data gathered by their phone

Today’s ecosystem of personalized online content is powered in great part by smartphone apps, many of which are constantly collecting data about their users. For consumers, it can be hard to tell how much they’re collecting and where it’s going. A prior study from Pew Research Center confirmed what many of us might think: that a majority of Americans are concerned and confused about data privacy. Many people felt a lack of control over their personal information and how companies are able to use it. Taking this research into account, we wondered what would happen if we tested mobile app users’ knowledge of their smartphone’s management of their data. Would their existing privacy concerns encourage them to take user agreements more seriously?

Key Takeaways

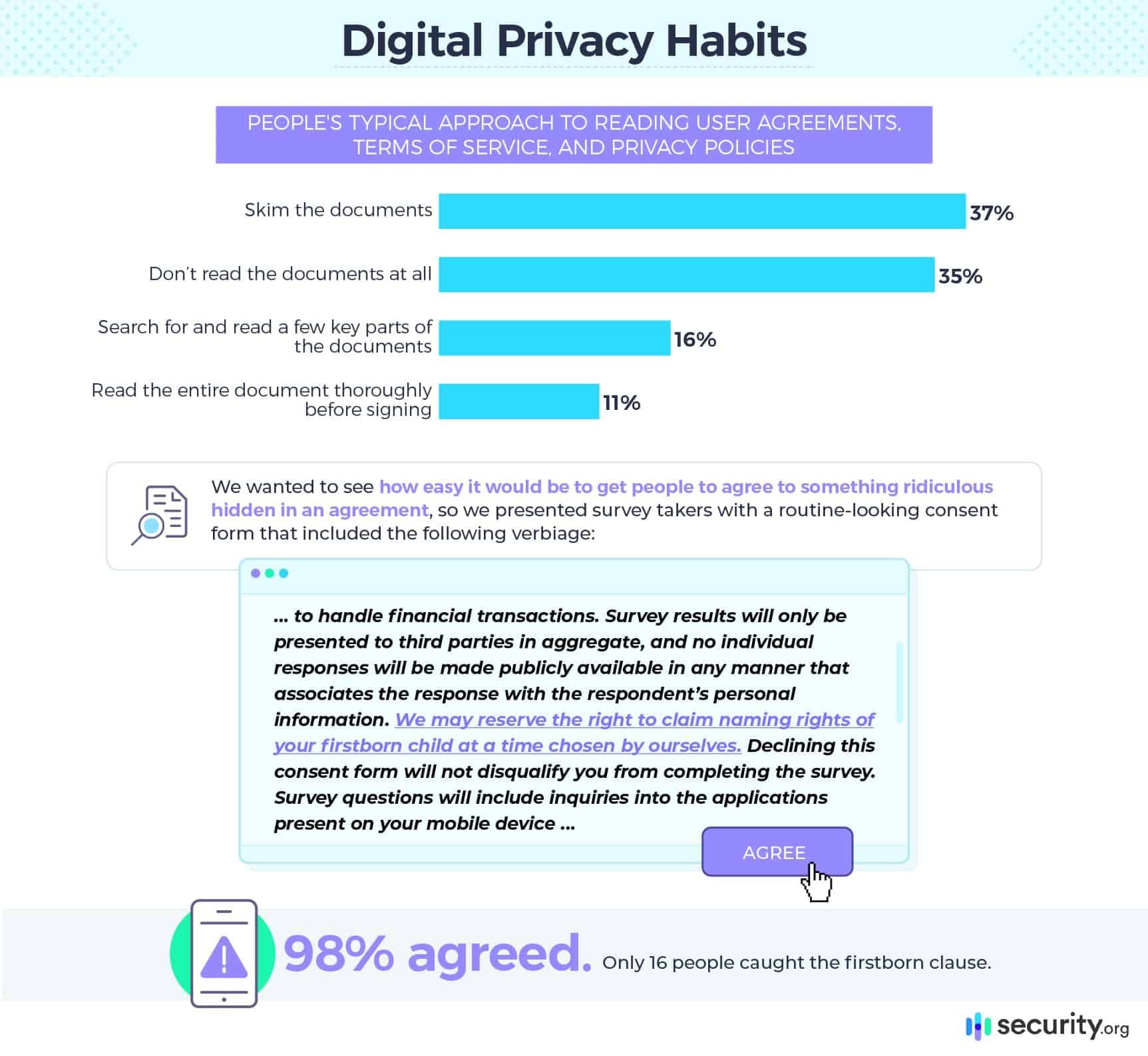

- The vast majority of Americans do not fully read privacy agreements before agreeing to them. 98% of respondents agreed to a fake consent form that offered the naming rights to their firstborn child. Less than 2% caught the prank.

- 100% of people who said they usually read user agreements, terms of service, and privacy policies thoroughly before signing wound up agreeing to our bogus consent form.

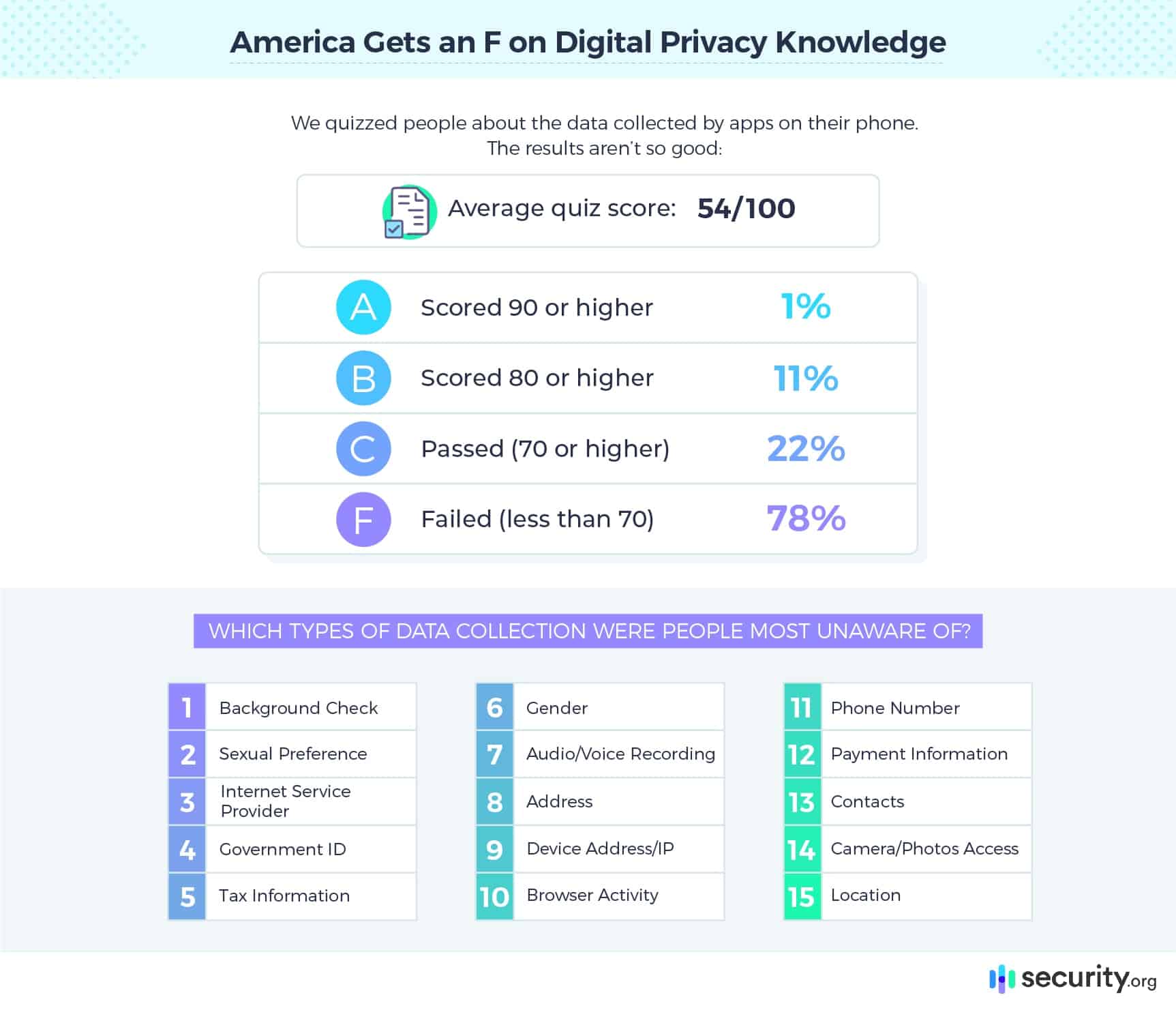

- On average, Americans were only able to correctly identify the types of data their phone gathers with 54% accuracy.

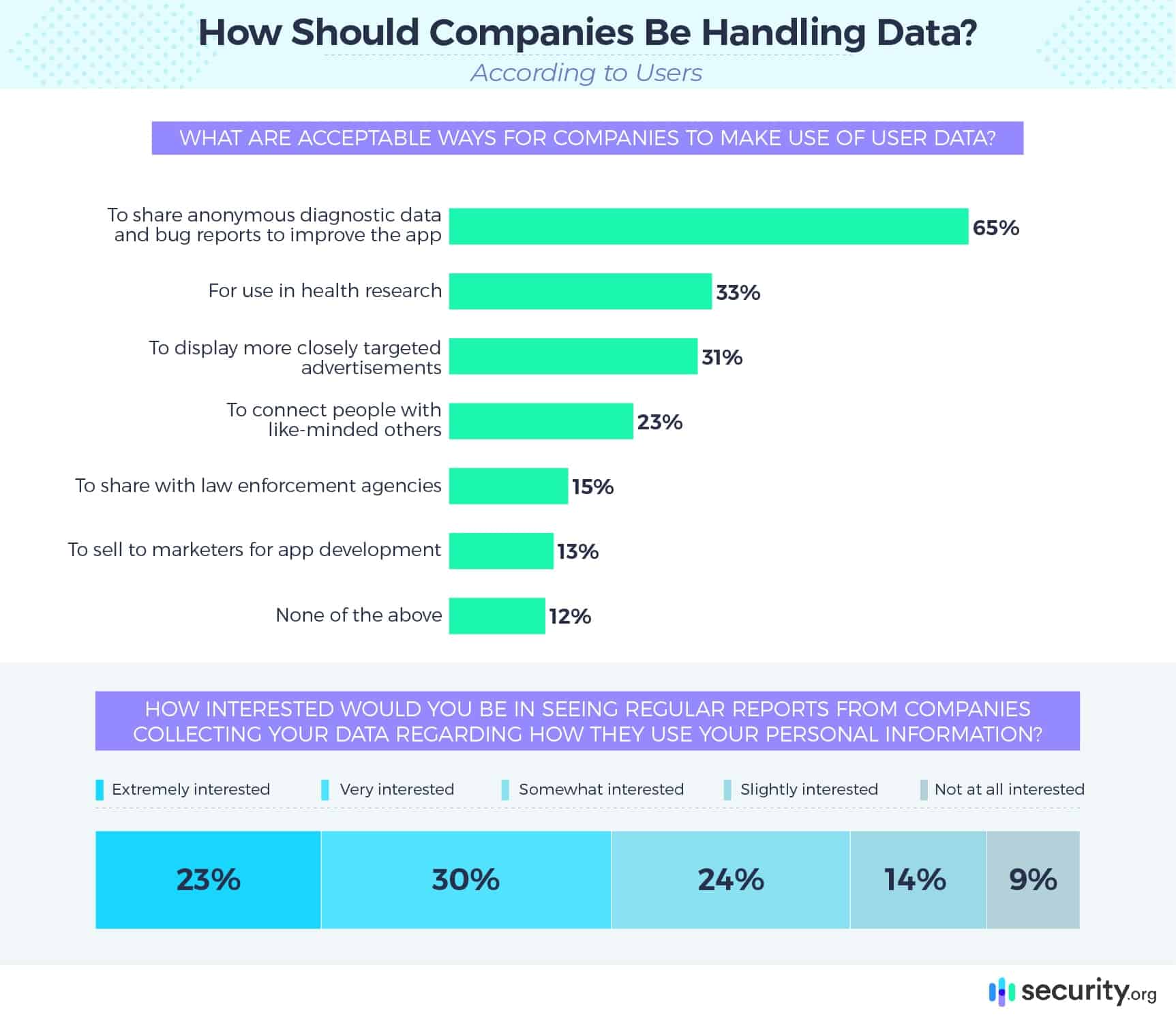

- In general, people were very interested in seeing what companies do with their data: 77% of people said they’d be interested in seeing regular reports from said companies on what’s being done with their personal data. 92% of respondents said these reports should be legally required.

Managing Cybersecurity

Smartphone users are responsible for managing their privacy online. But, understanding what you need to do in order to keep your privacy is a pretty big challenge. Maintaining your personal digital security and online safety requires a fairly deep understanding of your vulnerabilities. It also involves assessing the risks and understanding the consent forms of any new apps you install on your phone.

Do you think the average American understands what they’re signing up for everytime they download a new app? Let’s find out by taking a look at how Americans typically handle cybersecurity when downloading a new app.

Only 16 people (out of more than 1,000!) caught our sneaky clause in the dummy consent form at the beginning of our survey. Ninety-eight percent agreed to allow us to name their firstborn child, despite language in the consent form notifying them that they could still complete the survey if they declined. Even the 11% who claimed they typically read user agreements, terms of service, and privacy policies thoroughly before signing didn’t catch on: 100% of those respondents agreed to our fake consent form.

Learn More: To find out how you can protect yourself online, read our cyber security tips.

This portion of our study confirms the results of a similar experiment conducted by a group of researchers prior to ours. They also discovered it was very easy to get people to agree to absurd things, like giving up their firstborn child as payment or permitting the app to deliver all data to the NSA. The study concluded that only 9% of people actually read terms and conditions, with that number plummeting to 3% among younger people from ages 18-34.

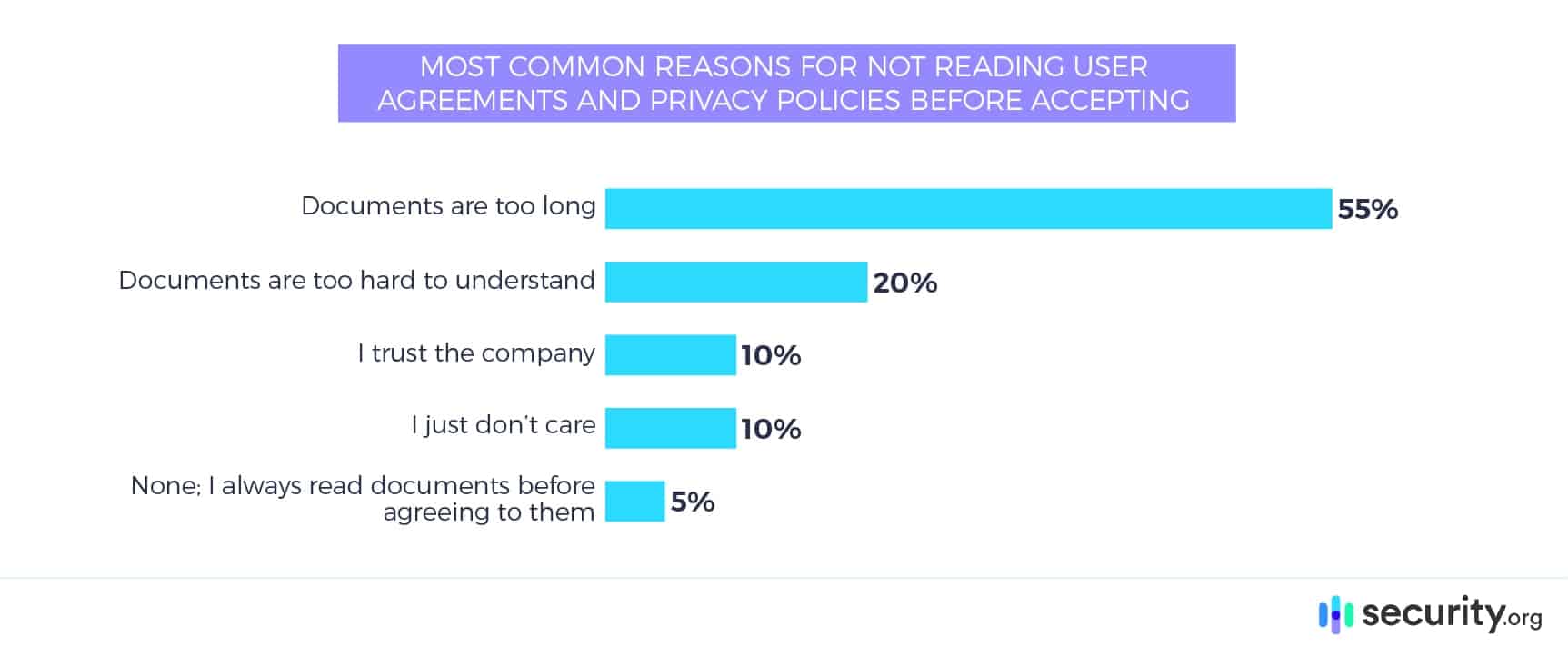

According to our data, the most common reason people don’t want to read such agreements is because they’re too wordy. With many services bearing privacy policies and user agreements with word counts in the thousands, it’s no wonder that so many Americans skip the fine print when downloading an app. According to Statista, reading Microsoft’s Terms of Service alone would take well over an hour. By comparison, you could read the entirety of the Art of War by Sun Tzu and still have some time to spare.

Digital Privacy Quiz

The next part of our study tested people’s knowledge about the different types of data their devices track. How aware are Americans about the private information they’re sharing? Take a look at their eye-opening quiz results below.

To determine America’s digital privacy score, we asked people to correctly identify the types of information the apps on their phone collect from them. We based it on the apps they said they currently have installed. The huge number of people who failed this quiz – 78% – revealed a wide knowledge gap between Americans’ perceptions of the data their phones track and the information they actually track.

FYI: Wondering if your password hygiene is up to snuff? Use our secure password checker for free.

Data Usage

Many companies collect a large amount of data about their users, which begs the question: What should these businesses be allowed to do with the information? Here’s how most Americans think their data should be used.

Most Americans were interested in regular data usage reports to see what companies are doing with their personal information. A strong majority believed this practice should be the law: 92% of people felt companies should be required to prepare reports on what is done with user data. Federal data privacy legislation would need to be passed to make reports like these the norm across the country.

The EU already maintains legislation that requires data transparency through the General Data Protection Regulation. Any data subject can request a full report on how their data gets used by the company. This report needs to also include justifications for why their data was processed. Whether or not laws like these will come to the United States is yet to be seen, but individual states continue to grow their data privacy requirements with legislation like the California Consumer Privacy Act.

Data privacy protection in the U.S. is currently a hodgepodge of state and federal laws that are often sector-specific. While there is no single regulation in place, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Act protects consumers from unfair or deceptive practices. For example, the FTC is authorized to take action against a company that fails to implement or maintain reasonable data security measures. They also protect Americans from companies that transfer personal information in a way that’s not disclosed in the app’s privacy policy. States have also enacted their own data privacy legislation such as the California Consumer Privacy Act and the Colorado Privacy Act. Currently, 13 states have signed some type of data privacy requirements into law.

Many Americans, including government leaders, seek to improve and standardize data privacy practices in the U.S. through federal legislation. They’re pushing for the passage of a comprehensive federal data privacy law to benefit both consumers and businesses.

Support for Data Privacy Legislation

We concluded our research by asking people how they feel about data privacy laws, especially if new legislation would affect personalized advertising on their social media feeds.

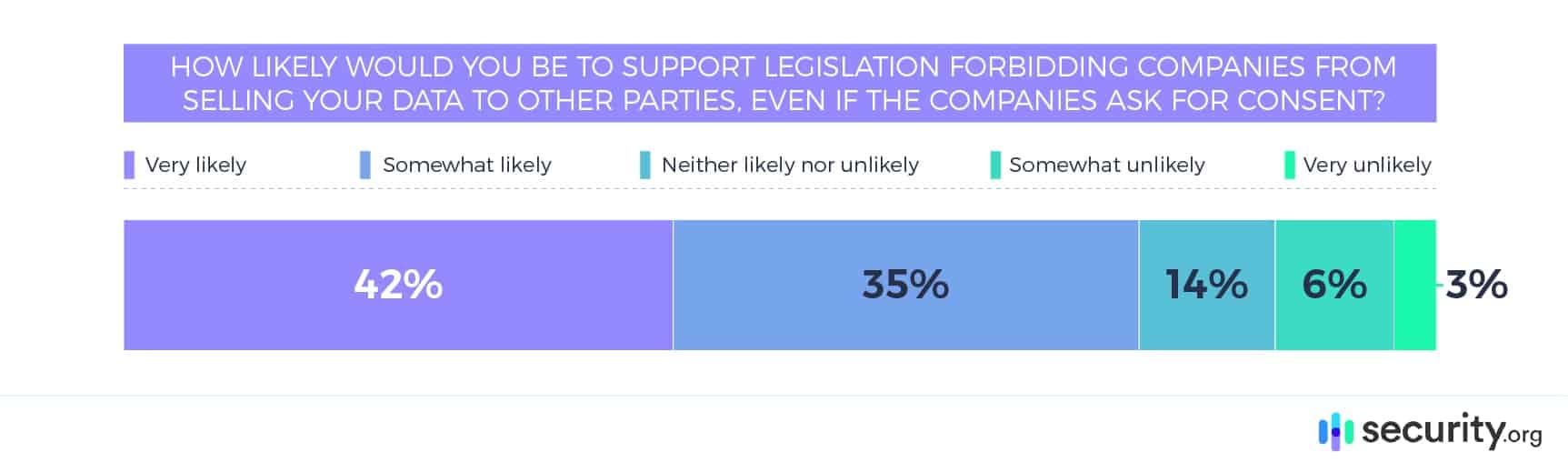

Most Americans would support a policy that would keep companies from selling their personal data, even though it could cause a disruption of personalized or targeted advertising on their online and social platforms:

- 77% of Americans would be likely to support such a law, while only 8% said they would be unlikely to do so.

- Three out of 4 people who said they like their social media feeds to be tailored to them also said they’d support this legislation.

- 75% of those who said they like personalized advertising also said they’d support this legislation.

These findings seem to indicate that people prioritize data privacy over convenience; however, this may just be lip service given that our earlier findings show that people can’t or won’t invest enough time in their privacy to read the fine print. A more likely conclusion is that people generally don’t fully understand the vital connection between user-data trafficking and personalized content. Americans are caught in a tug-of-war between convenience and privacy, and we can’t seem to make up our mind.

Conclusion

The majority of Americans are very concerned about data privacy; however, these feelings didn’t affect how much attention most people paid to our consent agreement. We were able to fool almost the entire group into allowing us the privilege of naming their firstborn child. In the near future, terms of service agreements may be governed by federal regulation to help users better understand what they’re signing. In the meantime, smartphone users can take advantage of the many different ways they can currently enhance their personal digital security.

Our Data

Data used in this analysis were gathered from a survey of 1,011 American smartphone owners. Approximately, 52% were men, 47% were women, and less than 1% were nonbinary or nonconforming. The average age of respondents was 36.9 years with a standard deviation of 12.4. Millennials are overrepresented in the sample, with 56% of respondents being born between 1981 and 1997. 25% were Generation X, and 13% were baby boomers. The remaining 6% were from Generation Z or from generations older than Generation X.

The experiment with the fake consent form was designed in such a way that if a respondent noticed the bogus clause, they were very likely to see the next sentence which informed them that declining the form would not disqualify them from completing the survey. This was done to reduce risk that respondents would notice the bogus clause and decide not to complete the survey.

Quiz scores were determined by checking the types of data collected by apps the respondent indicated they have on their phone against the types of data respondents thought their phones gathered from them. Correctly identifying that their phone did or did not gather a piece of data resulted in an addition of 1 point to their score. “Don’t know” responses did not count toward a positive score. Since there were 15 data types included in the survey, the maximum possible score was 15/15 (100%).

A primary limitation of this survey is reliance on self-report, which is faced with several issues, such as exaggeration, telescoping, and recency bias.